This topic always gets heated, and raises so many questions. Can you get enough protein without eating meat? Do we need animal protein for health reasons? Is animal protein more complete than plant protein? Is too much animal protein harmful? The list goes on. In this article I will go through the numbers that fairly conclusively put to bed some of these questions.

Why the focus on protein?

Our muscles are an organ. A very important organ that often doesn’t get talked about as one. Building and maintaining sufficient muscle mass and health is a critical pillar of longevity and health. It’s not just about being strong or looking good, but healthy muscle plays a key role in regulating so many parts of our physiology. With this in mind, I think it should be everyone’s goal to build and maintain more muscle, and to achieve this goal one requires sufficient protein intake in our diets.

So how much do I need?

The daily recommended protein intake (RDI) according to UK government guidance is 0.8g/kg body weight. This is (as expected by now!) the bare minimum amount of protein we need to not become malnourished. It’s not indicative of optimal levels for your body to work like a slickly oiled machine on a cellular level. Furthermore, the RDI is too generic to be able to use at face value because your personal requirements will depend on your body composition, your goals, age, to name a few relevant factors.

It is well documented that to maintain and certainly build this all important organ, our musculature, we need at least 1.2g/kg but more likely 1.6-2g/kg of body weight. So many people would not even come close to this amount without being mindful and intentional of it. The British Nutrition Foundation states the the average protein intake for adults aged 19-64 years is 76g/day – which would only be the optimal 1.6g/kg if you weighed around 48kg!

Where to get my protein from, animals or plants?

So in all honesty, I started writing this article with somewhat of a bias, expecting that animal protein is likely to prove a better, higher quality source of protein for muscle health. Interestingly, I was pleasantly surprised with the conclusion of my deep dive into the data.

To start, below are two tables of the top 10 plant and animal based protein sources, sorted by protein content per serving which is a key metric to take note of here.

| Food Item | Protein (g/100g) | Average Serving Size (g) | Protein per Serving (g) |

| Seitan | 75.0 | 85 | 63.8 |

| Soybeans | 36.5 | 100 | 36.5 |

| Pinto Beans | 21.4 | 171 | 36.6 |

| Black Beans | 21.6 | 172 | 37.1 |

| Chickpeas | 19.0 | 164 | 31.2 |

| Kidney Beans | 24.0 | 133 | 31.9 |

| Lentils (Cooked) | 9.0 | 198 | 17.8 |

| Edamame (young soybeans) | 11.2 | 155 | 17.4 |

| Tempeh | 19.0 | 85 | 16.2 |

| Quinoa (Cooked) | 4.1 | 185 | 7.6 |

| Food Item | Protein (g/100g) | Avg. Serving Size (g) | Protein per Serving (g) |

| Tuna | 29.0 | 154 | 44.7 |

| Salmon | 25.4 | 154 | 39.1 |

| Haddock | 24.2 | 154 | 37.3 |

| Chicken Breast | 31.0 | 120 | 37.2 |

| Halibut | 22.9 | 154 | 35.3 |

| Turkey Breast | 29.0 | 120 | 34.8 |

| Tilapia | 26.0 | 113 | 29.4 |

| Lobster | 19.0 | 145 | 27.6 |

| Cod | 18.0 | 154 | 27.7 |

| Venison | 30.2 | 85 | 25.7 |

| Bison | 28.4 | 85 | 24.1 |

As you can see, there are plenty of options in both categories to get a good dose of protein from plants or meat. No need for further debate right? Ah but if only it was that straightforward.

The important point to highlight here is the difference in calories between the plant proteins and animal based sources. The tables below are the top 5 foods from each category comparing the calories that come along with a portion of the food.

| Food Item | Protein per Serving (g) | Calories per Original Serving Size |

| Seitan | 63.8 | 314 |

| Soybeans | 36.5 | 446 |

| Pinto Beans | 36.6 | 593 |

| Black Beans | 37.1 | 586 |

| Chickpeas | 31.2 | 597 |

| Food Item | Protein per Serving (g) | Calories per Serving |

| Tuna | 44.7 | 203 |

| Salmon | 39.1 | 317 |

| Haddock | 37.3 | 139 |

| Chicken Breast | 37.2 | 198 |

| Halibut | 35.3 | 171 |

Calories matter

This is where a big challenge lies in getting protein from solely plant based sources. According to government statistics in the UK in 2023, 64% of adults (two thirds!) were overweight or obese (by BMI measurement). This means that for the large majority of the population, calories matter!

The highest plant based sources of protein (excluding seitan which is an anomaly in this case) come with a much higher density of calories per serving. For example, an average serving of chickpeas with 31g of protein would come with almost 600 calories compared to 198 calories per serving of chicken with 37g of protein. This is not a small difference if we extrapolate across a long period of time.

We’ve all heard of athletes and muscular individuals who are vegan or vegetarian and will claim they can get more than enough protein from plants alone. They are indeed right, but this works for them because their daily calorie requirements based on their level of activity is so much higher than the average person that they can absorb and tolerate the extra calories. Most people who are not training competitively, or even hard, will struggle to handle the extra calories that will very likely lead to further problems with weight gain.

What about amino acids and “quality” of protein?

Another debate point in the battle between animals and plants is whether one is a more “complete” source of all the amino acids than the other, or does one contain more of the essential amino acids than the other? Are certain amino acids more important for muscle protein synthesis?

Amino acids are the building blocks of protein. Think of them as the individual Lego pieces that make up the bigger building, the protein. There are 20 different amino acids, 9 of which are considered “essential”, meaning that we must obtain them from external sources as the body cannot make these from other building blocks.

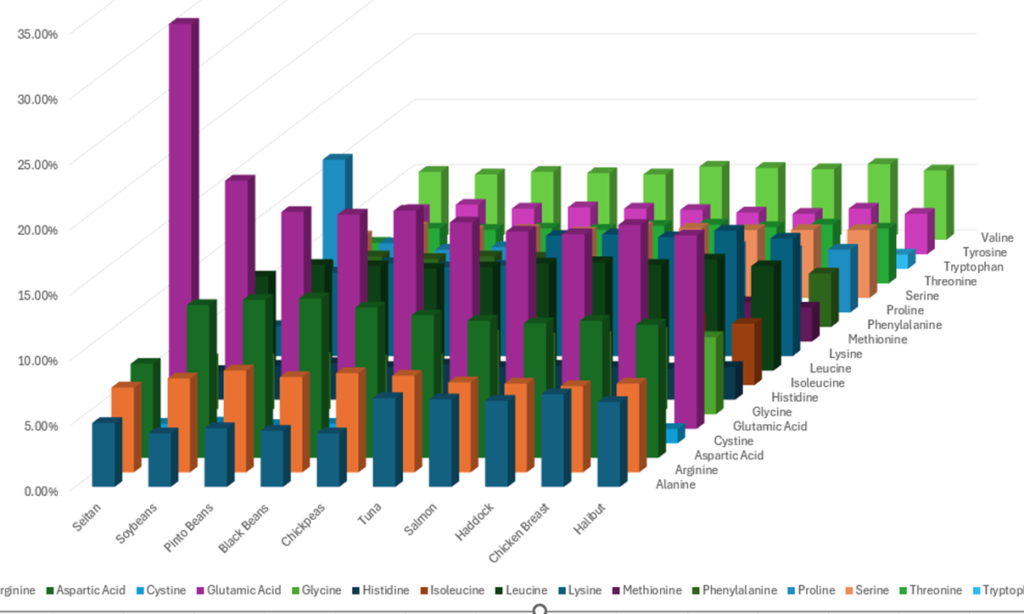

Below is a chart comparing the amino acid composition of the same protein sources in the tables we discussed earlier. This chart can get a little mind boggling to interpret so if this looks like an optical illusion to you, read past the chart below for my summary.

An easy way to draw conclusions from the chart above is to run your eyes along any given row of columns and see if the first 5 (plant proteins) are drastically different from the second 5 (meats). If they are not that different, it means the percentage of that amino acid is largely the same across the plant proteins and meat sources of proteins of this table.

As you can see, there is not a lot in this competition when it comes to amino acid composition. Plant based sources have largely a very similar composition by percentage of each of the amino acids as do animal proteins. There are however a few important differences:

Animal sources are higher in:

- Lysine – 11% vs 7% (for most plant proteins, excluding seitan which is lower)

- Methioinine – 2.7-3.1% vs 1.7% – a much smaller absolute difference

- Leucine and Isoleucine: These branched-chain amino acids are slightly higher in animal proteins, but the difference is even less meaningful compared to the already fairly minor differences above.

The king of plant protein sources, seitan, has a stark advantage over animal based sources in that it has a much higher percentage of the amino acid glutamate (31%) compared to animal sources (16-20%). Tempeh is also higher in glutamate than animal sources of protein.

To revert to my Lego analogy again – it is shown that if you have sufficient numbers of the right essential building blocks (amino acids), then the rate at which you can build (muscle) depends not on the number of pieces (amino acids) but on how fast the person could put them together (in the body this refers to the machinery that builds proteins in cells). If you look at the table above, all amino acids marked with * (essential) have largely similar concentrations by percentage across plant proteins and meat. There is one exception, methionine, but this difference is small in absolute numbers that it is unlikely to represent a significant problem.

Ultimately, this is all much of a muchness, as all amino acids have their role in health in different ways. We need them all. Plant based sources are in fact almost as good sources of all amino acids with a few small differences, which can be easily overcome by eating sufficient protein from a diverse source of plants.

It’s not ALL about protein

Now reducing your decisions around foods to just their protein content is a bad strategy for overall health. Protein is only one aspect of any nutritional strategy and we can not just optimise for this macronutrient alone. Looking at the overall value of a food, we must consider its fibre content, phytonutrient density, vitamin and mineral content.

Perhaps the most important difference between plant protein and meat is the fibre content. Consuming sufficient fibre is one of my key recommendations of almost every nutritional strategy and in this regard, plants protein wins hands down.

On the other hand, oily fish are rich in omega-3 fats which you would struggle to find in the same quantity in any of the plant protein sources. Some meats however come with a high level of saturated fats which can contribute negatively to your overall health. As you can see, you have to look at the bigger picture.

So which is right for me?

How does one bring all this confusion and conflict together for themselves? Like with most things with nutrition, it’s about personalisation, balance and overall quality of foods you consume. I like to recommend people consume protein from a variety of good quality meat and plant-based sources in a way that also meets their other macro and micronutrient goals.

There is no one size fits all, as everyone will have different goals and personal requirements. This is why we perform such comprehensive testing and assessments on our clients before giving them a personalised nutritional strategy to support their longevity goals.

It is important to consider that in order to enjoy this variety, people need to have the knowledge and time to prepare and cook these ingredients. I find that the relative unfamiliarity that people have with preparing and cooking using certain plant based proteins, leads to the misconception that there are not as many good plant based protein sources or that it’s more difficult to get sufficient protein from plants alone.

However, if there is anything that all this mind numbing analysis can put to bed is that on the whole, we don’t need to worry about whether your protein comes from meat or plants, just ensure you get enough of it!

Contact us for a comprehensive assessment of your nutritional status and let us give you a tailored nutrition plan aligned and optimised towards achieving your health and longevity goals.